Bilingual Education

Second Language Learners - Alternative Language Learners - ESL

Questioning is the basis of all learning.

Overview

- Introduction

- Culture model

- Two analysis of public debate on bilingual education

- Definitions & analysis

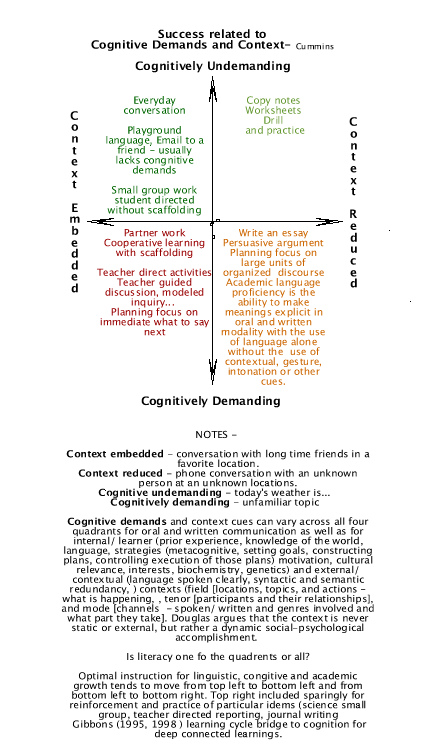

- Cognitive & contextual demands quadrants

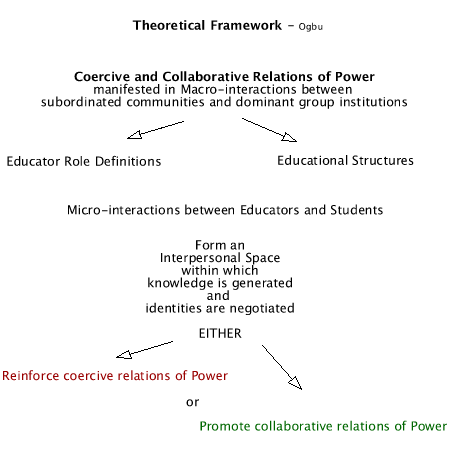

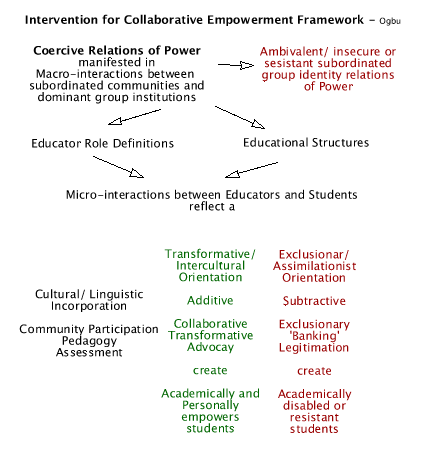

- Intervention Framework to promote collaborative or coercive relationships

- Interventions framework to collaborative empower or disable learners

- Cummins claims for Policy decision making

- Stages of Second Language Acquisition

- Stages for 2nd language acquisition & tiered learning prompts

- Planning

- Tiered Language Acquisition Questioning Plan - Coyote and Anansi

- Resources

- Our brains can adapt to accents

- Study guide for With Literacy and Justice for All

- Internet links - Edelsky

Introduction

Literacy for all is a goal, which includes many English language learners and multi language learners who are being educated in English as their second language. This page explores positive and negative ideas associated with this (bilingual education) and possible curricula necessary to achieve literacy in a second and multiple languages.

Topics include: two analyses of public debate on multilingual literacy, definitions related to language acquisition of bilingual learners and English language learners: common underlying proficiency (CUP), interdependence principle, separate underlying proficiency, threshold hypothesis, developmental and interdependence hypothesis.

Also, cognitive and contextual demands are compared within quadrants to show their interrelationship with communication and kinds of successful instructional interactions. An intervention framework to promote collaborative or coercive relationships and an interventions framework to collaboratively empower or disable learners. And a framework for policy Decisions.

Stages of second language acquisition, stages for 2nd language acquisition & tiered learning prompts. And a tiered language acquisition questioning plan.

Resources include a study guide for With Literacy and Justice for All and some Internet links.

Language learning

Learning language and developing literacy are highly culturally and environmentally dependent. To deny their relationship and power to support each other in learning is essential. The iceberg model of culture suggest how interrelated culture is to our being and hopefully strongly suggests the importance of the integration of language and culture to facilitating literacy.

Culture model: Iceberg concept of culture

Public debate & bilingual education two examples

The public often use misinformation as common sense facts to debate educational issues. Let's look at two examples as they relate to bilingual education and Second Language Learning (SLL).

The first example is a paragraph from an article written by John Micklethwait in, The Economist.

Excerpt from The Economist, by John Micklethwait from 11-17 March:

New York is the next target for Ron Unz, a Silicon Valley millionaire who was the guiding force behind California's Proposition 227. This measure replaced bilingual education, which around half the students with poor English were receiving, with crash courses in English. Bilingual education, originally invented as a way to steer funds to poor people in the southwest, has always produced disappointing results. It is now merely a sop to the teachers' unions. Since bilingual education was banned in California about a year ago, test scores have risen. Even more tellingly, the students who were put on the English crash course or into mainstream classes are well ahead of those still stuck in bilingual ones (which a few students have waivers to continue). (2000:15)2

Let's analyze Micklethwait's claims.

• Prior to Proposition 227, only 30% of English language learners in California were in any form of bilingual program and less than 20% were in classes taught by a credentialed bilingual teacher.

• Bilingual education was not originally 'invented' in the United States-these programs have been operating since Greek and Roman times. Furthermore, the spread of these programs in countries around the world, including the spread of dual language programs in the United States, is hardly consistent with the claim that they have 'always produced disappointing results' (see Baker & Prys Jones, 1998).

• Contrary to the claim that bilingual education is a 'sop' to teachers' unions, teachers unions in California and elsewhere have tended to be very ambivalent about bilingual education for the simple reason that only a small fraction of their members are in fact bilingual teachers.

• The implication that test scores rose in California as a result of the banning of bilingual education is without foundation. Changes in scores occurred in districts in ways that appeared to be completely unrelated to what kind of program a district implemented (Hakuta, 1999).

• There is absolutely no data to support the claim that students put into all-English classes made better progress than those who were 'still stuck in bilingual ones' (Hakuta, 1999).

Adapted from Cummins, J. (2000), Language, power, and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters

A second example takes quotes journalists have often pulled and used from a book written by Arthur Schlesinger Jr. and includes evidence found by J. Cummins to analyze them.

Arthur Schlesinger Jr.'s Quote is Simply Inaccurate

Bilingualism shuts doors. It nourishes self-ghettoization, and ghettoization nourishes racial antagonism. ... Using some language other than English dooms people to second-class citizenship in American society. ... Monolingual education opens doors to the larger world. ... institutionalized bilingualism remains another source of the fragmentation of America, another threat to the dream of 'one people'." (1991: 108-109)

Arthur Schlesinger Jr.

- Students in Kenya spoke English as a second or third language as well as they might speak Kiswahili, Gujerati, or Kikuyu. As an instructor in both countries Cummins found Kenyan students, with Down Syndrome, spoke receptive and expressive language proficiently in their third language (English) equivalent to that of the US monolingual English students with Down Syndrome (Cummins, 2000).

- Summary of California data by Gandara (1999)

concluded:

Listening skills are at 80% of native proficiency by grade 3. Reading and writing skills remain below 50% of those for native speakers. Not until after grade 5 do different sets of skills begin to merge. Students may be able to speak and understand English at fairly high levels of proficiency within the first three years of school, however, the academic skills in "English" reading and writing, take longer for students to develop.

Two big reasons for a difference - Social skills are less complicated to learn and come with more environmental cues than learning academics which have fewer environmental cues. The other big difference is L1 [one language] learners are not sitting and waiting, but are also progressing. - Poor children get off to a bad start before they are born. Their mothers get prenatal care later, if at all, which can impair intellectual functioning. They are also more than three times as likely as non-poor children to have stunted growth. They are about twice as likely to have physical and mental disabilities, and are seven times more likely to be abused or neglected. And they are more than three times likely to die (USA Today 1999: 19A Gerald W. Bracey)

- The child poverty level in the United States is more than 20%, substantially higher than any other industrialized nation. This makes America uniquely handicapped because of the massive amounts of poverty. As long as this is tolerated, how can education reform work?

- When students conversational English is “caught up”, then the perception of the teachers is - "Why aren't students doing better academically?" They are unaware of the three year lag that exists between having skills for language and having skills for academic growth, which can explain and may attribute lack of success to variables other than the child.

- Fully bilingual Hispanics earn nearly $7 000 per year more than their English only counterparts (Latino link yahoo.com).

Adapted form Cummins, J. (2000), Language, power, and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

A good introduction to reflect on what you know about Language and literacy is read Edelsky's With Literacy & Justice for All. Below is a study guide.

ESL related definitions & analysis

Additive bilingualism

Additive bilingualism is is when a learner's first language continues to be developed while they're learning a second language. As opposed to Subtractive bilingualism, when a learner learns a second language at the expense of their first language.

The linguistic and academic benefits of additive bilingualism for individual learners provide an additional reason to support students in maintaining their first language while they are acquiring English. Not only does maintenance of a first language help students to communicate with parents and grandparents in their families, and increase the collective linguistic competence of the entire society, it enhances the intellectual and academic resources of individual bilingual students. At an instructional level, we should be asking how we can build on this potential advantage in the classroom by focusing the learners' attention on language and helping them become more adept at manipulating language in abstract academic situations.

Common underlying proficiency (CUP)

Common underlying proficiency (CUP) is the cognitive academic proficiency that underlies academic performance in both languages (Cummins 2000: p. 38).

Research data:

• In virtually every bilingual program, that has ever been evaluated, whether intended for linguistic majority or minority students, spending instructional time teaching through the minority language entails no academic costs for students' academic development in the majority language (Baker, 1996; Cummins & Corson, 1997).

• An impressive number of research studies have documented a moderately strong correlation between bilingual students' first language and second language literacy skills in situations where students have the opportunity to develop literacy in both languages. It is worth noting that these findings also apply to the relationships among very dissimilar languages in addition to languages that are more closely related, although the strength of relationship is often reduced (e.g. Arabic-French, Dutch-Turkish, Japanese-English, Chinese-English, Basque- Spanish) (Cummins, 1991c; Cummins et al., 1984; Genesee, 1979; Sierra & Olaziregi, 1991; Verhoeven & Aarts, 1998; Wagner, 1998).

• A comprehensive review of US research on cognitive reading processes among ELL students concluded that this research consistently supported the common underlying proficiency model:

• United States ESL readers used knowledge of their native language as they read in English.

• Native-language development can enhance ESL reading. (Fitzgerald, 1995:181)

Within a bilingual program, instructional time can be focused on developing students' literacy skills in their primary language without adverse effects on the development of their literacy skills in English.

• The relationship between first and second language literacy skills suggests that effective development of primary language literacy skills can provide a conceptual foundation for long-term growth in English literacy skills. This does not imply, however, that transfer of literacy and academic language knowledge will happen a

automatically; there is usually a need for formal instruction in the target language to benefit a cross-linguistic transfer.

Summary - If skills from one language transfer to learning another, then CUP skills will help.

Interdependence principle

The interdependence principle suggests interdependence of first and second languages is as follows.

To the extent that instruction in LanguageX is effective in promoting proficiency in LanguageX, transfer of this proficiency to LanguageyY will occur provided there is adequate exposure to LanguageyY (either in school or other environments) and adequate motivation to learn LanguageY. (Cummins, 1981a p. 29)

Separate underlying proficiency (SUP)

Separate underlying proficiency (SUP) are skills from one language which do not transfer to learning another. Therefore, they will not learning a second language.

Threshold hypothesis

Threshold hypothesis is the level of linguistic competence that must be attained in each language in order for bilinguals to avoid cognitive deficits and benefit cognitively from their bilingualism (Cummins, 1979, p. 229).

Developmental interdependence hypothesis

Developmental interdependence hypothesis is the level of 2ndLanguage competence which a bilingual learner attains which is a partially function of the type of competence the child has developed in 1stLangugage at the time when intensive exposure to 2ndLanguage begins (Cummins, 1979, p. 233).

Cognitive and Contextual Demands Quadrants

(adapted from Cummins)

Intervention Framework

Intervention for Collaborative Empowerment Framework

Cummins claims for policy decision making (2000)

A substantial research and theoretical basis for policy decisions regarding minority students' education does exist. In other words, policy-makers can predict with considerable confidence the probable effects of bilingual programs for majority and minority students implemented in very different socio political contexts.

- They can be confident that if the program is effective in continuing to develop students' academic skills in both languages, no cognitive confusion or handicap will result; in fact, students may benefit in subtle ways from access to two linguistic systems.

- They can predict that bilingual/ELL students will take considerably longer to develop grade-appropriate levels of L2 academic knowledge (e.g. literacy skills) in comparison to how long it takes to acquire peer-appropriate levels of L2 conversational skills, at least in situations where there is access to the L2 in the environment.

- They can be confident that for both majority and minority students, spending instructional time partly through the minority language will not result in lower levels of academic performance in the majority language, provided of course the instructional program is effective in developing academic skills in the minority language. This is because at deeper levels of conceptual and academic functioning, there is considerable overlap or interdependence across languages. Conceptual knowledge developed in one language helps to make input in the other language comprehensible.

- These psycho-linguistic principles by themselves provide a reliable basis for the prediction of program outcomes in situations that are not characterized by unequal power relations between dominant and subordinated groups (e.g. L2 immersion programs for students from dominant language backgrounds). However, they do not explain the considerable variation in academic achievement among culturally and linguistically diverse groups nor do they tell us why some groups have experienced persistent school failure over generations.

- Why students choose to engage academically or, alternatively, withdraw from academic effort is to acknowledge that human relationships are at the heart of schooling.

- Relationships dominate all participant discussions about schooling in the US. No group inside any school surveyed felt adequately respected, connected or affirmed. Students repeatedly referenced a need for care. What they liked best was when teachers cared about them or did special things for them. Their least liked things included being ignored, not being cared for, and negative treatment. (Popllin & Weeres, 1992: 19)

Stages of Second Language Acquisition

Source - Classroom Instruction that Works with English Language Learners Participant's Manual (McRel)

Key Ideas

- Students acquiring a second language progress through five predictable stages.

- Teachers who are effective with ELLs provide instruction that

- reflects their students' stages of second language acquisition.

- supports students moving forward in language acquisition levels.

- engages ELLs at all stages of language acquisition in higher level thinking activities.

Background

Anyone who has been around children who are learning to talk knows that the process happens in stages from understanding to one-word utterances, two-word phrases, full sentences, and eventually, complex grammar.

This progression can be categorized for students learning a second language in five predictable levels (Krashen and Terrell, 1983).

Levels of language acquisition

Levels of language acquisition include:

- Preproduction - Students can point to a picture in the book as the teacher says or | asks: "Show me the wolf. Where is the house?"

- Early Production - Students do well with yes/no questions and one- or two-word | answers: "Did the brick house fall down?" "Who blew down the straw house?"

- Speech Emergence - Students can answer questions with phrases or short-sentence answers, Students can respond to "why" and "how" and "explain" prompts: "Explain why the third pig built his house out of bricks." "What does the wolf want?"

- Intermediate Fluency - Students can answer "What would happen if and "Why do you think" questions in longer sentences: "Why do you think the pigs were able to outsmart the wolf?" "Why could the wolf blow down the house made of sticks, but not the house made of bricks?

- Advanced Fluency - Students can retell the story, including the main plot elements and leaving out the insignificant details.

Progression is influenced by many factors: learners amount of formal education, background experiences, level of parent education, length of time they've been in the U.S., affective factors, ...

An important component of helping ELLs is to provide instruction within their level of language acquisition. Therefore, it is important to know each English language learner's language acquisition stage. Knowing and understanding this is critical to provide effective instruction.

A word of caution: even though there are similarities between the process of learning a first and second language, there are also some important differences: Children acquire their first language through exposure to the language and opportunities to use it. Exposure alone is not enough for second language learning, especially for older learners who need assistance in learning the functions, structures, and underlying cultural aspects of the language.

Once the student's level of language acquisition is known a teacher works within the learner's "zone of proximal development" - the area between what the learner is capable of independently at the moment and what the they can accomplish with the help of a knowledgeable other (Vygotsky, 1978). A teacher starts at the learner's current language level to help them move to the next level.

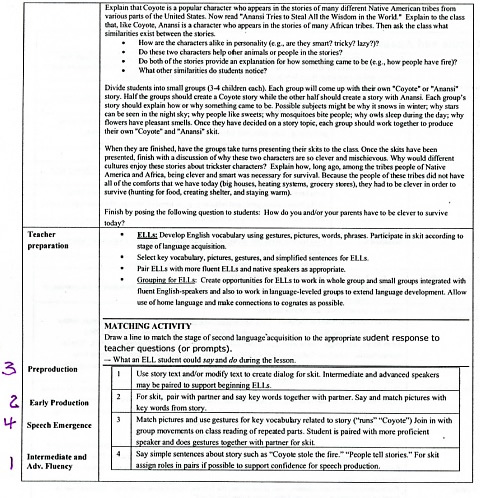

Stages of Second Language Acquisition and Tiered Questions Prompts

Stages of second language acquisition, characteristics of the student, approximate age of the specific language acquisition, and sample tiered questions prompts

| Stage | Characteristics of learners | Approximate age of specific language acquisition | Sample tiered question prompts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preproduction |

|

0 - 6 months |

|

| Early Production |

|

6 months - 1 year |

|

| Speech Emergence |

|

1 - 3 years |

|

| Intermediate Fluency |

|

3 - 5 years |

|

| Advanced Fluency |

|

5 - 7 years |

|

Planning tools

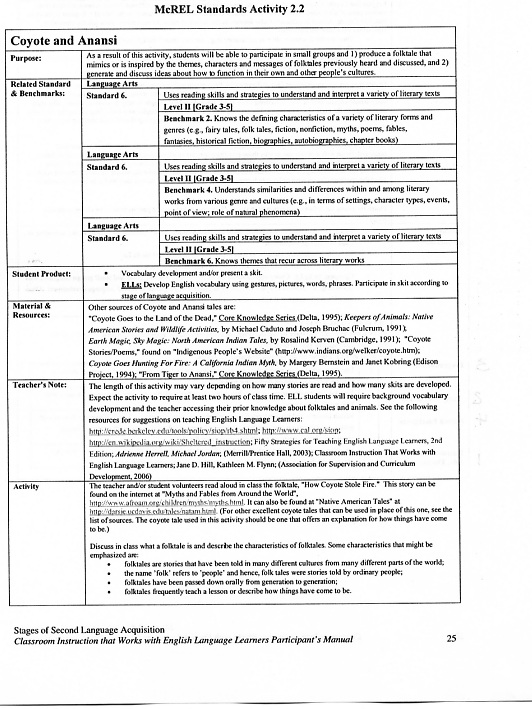

Sample framework and plan with Tiered Language Acquisition - For more samples see source - Classroom Instruction that Works with English Language Learners Participant's Manual

Tiered Language Acquisition Questioning Plan 2.2 - Coyote and Anansi

It is possible to help students simultaneously learn content knowledge and English language proficiency. To achieve this one must also consider other variables of learning content beyond language proficiency. For example teacher expectations and the level of learner engagement. Bloom's taxonomy, widely understood by teachers, can be used to show how understanding language proficiency can be used with other variables to create a better learning experience.

Example

Chart includes

- Content knowledge classified by Bloom's taxonomy

- Language Use across stages of second language acquisition (communication channels)

- Activities and outcomes.

The matrix allows activity outcomes to be placed in the intersecting cells for each possible combination.

Additional planning: McRel study of strategies that work with ESL students.

Resources

Our Brains Can Adapt to Accents

Crete news October 25, 2023

Pesante-Daniel

Johanna

Our brains can adapt to accents

I'm sure you've heard someone speak your native language with an accent. What is your reaction? What feelings does it provoke in you?

When a person speaks a second language, he or she usually speaks with an accent. A person who speaks with a particular accent and

pronounces the words of a language in a distinctive way can reveal which country, region or social class he or she comes from.

An accent is a change in the sounds of the second language, often resulting from the influence of the first language. For example, if the person pronounces the phrase "I need water" and another person (a Hispanic for example) says the same thing but pronounces the word water as "guater," the difference is one of accent.

Accents are not just the result of poor muscle coor-dination. Most speakers of a second language turn to the unconscious rule of their brain that they already know from their first language and that comes naturally on them.

This knowledge not only influences how a second language is spoken, but also how it is heard. Having an accent affect our ability to pronounce consonants and vowels in English or any other second language.

There are about 6,000 to 7,000 languages in the world and most people on the planet know more than one. When we start learning a second language as teenagers or adults, say at the age of 12, 20 or 30, we are likely to speak with an accent when we speak a second language.

This could be an indication that we are not born with an accent, but that it is caused by our environment.

It is important to understand that speaking with an accent does not necessarily mean that we are difficult to understand, as accents are the results of grammar that can affect the way we hear a language and not just the way we speak it.

In other words, when we hear someone speak with an accent, understanding is not necessarily affected and this is not a reason to impede the communication. However, at some point, we may have found it difficult to communicate with someone because the accent was so heavy that it sounded like the person was so heavy that it sounded like the person was speaking in their first language.

But, nevertheless, our brain is an amazing machine, it adapts when we interact with someone periodically and adjusts to the specifics on the accented speech of the person or persons.

In conclusion, bilingualism is a natural state of the human brain, even when we speak or listen with an accent. And as my late brother always told me, you can speak with an accent, but you don't think with an accent.

Study guide for With Literacy and Justice for All:

Rethinking the Social in Language and Education. third ed.

Carole Edelsky (2006) Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. NJ.

ISBN # 0-8058-5508-4

The book, With Literacy and Justice for All: Rethinking the Social in Language and Education by Carole Edelsky explains how culture can be a major barrier to developing a passion for reading. As you read Edelsky I hope you will be struck by her continual blasting of Cummins and all the references to second language learners. I was, so I stopped reading it and checked out - J. Cummins, read a couple of articles, and finally his book Language, Power, and Pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. (see references in notes for the book). After reading his book I understood what he was saying, but I could also see something I think in Edelsky’s book, With Literacy and Justice for All: Rethinking the Social in Language and Education that went beyond Cummins's ideas. So I went back to finish it. Since I had only gotten through the first four chapters I decided to start over in light of what I know knew what Cummins wrote. I found what Cummins wrote (see my notes on his ideas) was reasonable in a traditional sense, however Edelsky's complaints about Cummins’s work I think are accurate. I do not believe she misrepresented his ideas. Since that time Cummins has updated his ideas. It is this kind of discourse that is beneficial for all as it moves us forward in our understanding.

As I completed the book I saw clearly the value, concern, and urgency with which she writes. The relationships that must be understood if literacy is to be achieved by all. After a review of Cummins I was convinced some variables, which seemed insignificant and easily over looked, are indeed imperative to consider when discussing literacy development and academic success. The relationship of second language learning to literacy, whole language, and the need of the inclusion of social transactions in any definition of reading and writing and literacy for all learners is necessary. My experiences better helped me understood Edelsky’s passion and desire to have everyone understand her messages. For without this understanding we can not succeed in facilitating literacy for large numbers of our students at a level I believe we all desire. I am convinced it is imperative we understand the messages within this book if we are to advance literacy.

She throws a lot of vocabulary and acronyms into her writing so I encourage you to use a electronic dictionary and a cheat sheet to write notes, the book's related links if you desire more information, and the notes for Cummins as a reference.

If you are familiar with other resources that might any of the texts I selected, I would appreciate your sharing them with us.

Thanks.

Two quick articles to support the reading.

Focus questions for

Chapter 1

How does this chapter provide ideas on why children in school don’t have difficulty learning the school’s curriculum, have difficulty learning learning the school’s curriculum, or reject learning the school’s curriculum?

Chapter 2

Discuss the information in chapter 2 or review the following information and answer the question that follows.

Many children that will enter school in the fall were placed in front of educational videos often before they could sit. A recent study concluded Baby Einstein and other children shows purchased by parents to provide their children an educational advantage have found the expected gains did not materialize. The only significant edge attained by these children is an increase in their ability to recognize characters and other images. This talent can then be used by children for character and brand recognition used as hooks in marketing campaigns to make all sorts of products attractive to these children. For example Shrek is used in a national campaign for exercise and wellness. He is also used to market a number of foods a majority of which are not healthy. Another example of the power of this type of marketing was shown in a study that found children preferred vegetables and fruit offered to them packaged in Mac Donald's containers over those offered without the containers. It is unfair and naive to think that parents even with the best of intentions are able to guide any young child through a learning experience on how to become a smart consumer. Instead family relationships are stressed and children begin to think it possible to live healthy through fast foods. It is hypocritical for both the national government or any of the corporations to think otherwise. The marketing and business communities get what they want shop-o-holics and materialistic future consumers who believe you are valued by what you have.

How does the information in this chapter relate to this scenario and what implications does it have for schooling, teaching, and literacy?

Chapter 3

Review the principled procedures created for this class and literacy. Which were reviewed and changed by the class in the summer of 2005. Find ones that might be in need of change with respect to the information in this chapter. Make suggestions for changes along with a rational for those changes. Also create one that would be used to guide an advocate of literacy to promote literacy for ALL children no matter their backgrounds.

Chapter 4

Edelsky while critiquing the writings of Cummins is in my opinion critiquing the practice in schools today. Select one or two of her ideas in this chapter and tell why you agree or disagree with her ideas.

Chapter 5

Give an example of a class activity, not included in the book, that would facilitate literature literacy through reading, writing... that would not be considered an exercise. Include a discussion that would convince others that it is: literature literacy, reading/ not reading, not exercises/ exercises, and literates as-subjects/ not literates as objects. That its purpose is important. Literates as subjects relates to the social political not individual. With a look at who else is involved and how their role and power relates to the role and power of the literate and from where the print cues originate. Also include what goals/ outcomes might be possible for students to facilitate for their literacy development.

Chapter 6

Is becoming literate like learning to speak? Or is becoming literate more like learning a second language. Create a scenario for becoming literate. Present evidence to support its implementation and describe what is lost if it were not implemented. Evidence should include a rationale to support it which would encourage others to share with peers and the public to support change in yours and their school district.

Chapter 7

Whole language could have been undermined by the social political agenda of the elite or it could have theoretical flaws, or it there could be other reasons for its demise. Take a stand and provide a rationale for it.

Chapter 8

Review chapter 8 and 9. Reflect on the principled procedures and their consistency with respect to the ideas in the chapter. Select and identify principled procedures that might fit or need adaptation with respect to the ideas in the chapter. For example: goals, values, rules, and roles. Or create your own goals, values, rules and roles for your classrooms.

Chapter 9

Select an activity, describe it, how it might be implemented based on the four alternatives in chapter 9 and describe how each is applied or not.

Chapter 10

Reading to make sense with print has an 'essential' nature; it is - or requires - predicting based on cultural/ linguistic knowledge in the service of making meaning. We can not make sense of print without first identifying its key social features embedded in it and locating ourselves in relation to it. Find an example, analogy, or explanation that illustrates this idea in a manner that might help people that haven't read this book begin to think about the importance of the cultural social connections of literacy.

Chapter 11 and 12

If there isn't a time and place for literature in public schools, then why isn't this class irrelevant and a waste of time? Write a procedure or argument for professional action to attempt to increase the use of literature in the curriculum. Include a description on how you believe this relates to this chapter or information in the book.

Internet Links for Carole Edelsky (2006) With Literacy and Justice for All: Rethinking the Social in Language and Education. third ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. NJ. ISBN # 0-8058-5508-4

- Coles, G. (2000). Misreading reading: The bad science that hurts children. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Coles, G. (2001) Learning to read scientifically. Rethinking Schools, 15 (4), 3, 25.

- Coles, G. (2003). Reading the naked truth: Literacy, Legislation, and Lies. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Kennedy, R. (2004, March 8). The junk science of George W. Bush. The Nation.

- Kirsch, I., Jungeblut, A., Jenkins, L., & Kolstad, A. (1993). Adult literacy in America: A first look at the National Adult Literacy Survey. National Center for Education Statistics, NCES 93275. Retrieved from

- Kurtz, H. (2005, January 8). Administration paid commentator. Washington Post, p. AO1. Retrieved 2021

- Manzo, K. (2005, June 8). States report Reading First yielding gains; Some schools getting ousted for quitting. Ed Week. Retrieved 2021

- Ohanian, S. (2001, January). News from the test resistance trail. Phi Delta Kappan.

- Peterson, B. (1994). Teaching for social justice: One teacher’s journey: In B. Bigelow, L. Christensen, S. Karp, B, Miner, & B. Peterson (Eds.), Rethinking our classrooms, a special edition of Rethinking Schools (pp. 30-33, 35-38, Milwaukee, WI: Rethinking Schools.

- Quindlen, A. (2002, June 17). The destruction of literature in the name of children. Newsweek.

- Rich, F. (2005, June 12). Don’t follow the money. New York Times. Retrieved 2021

- Schemo, D. (2002, November 27). New federal rule tightens demands on failing school. Retrieved 2021

- Schemo, D. (2004a, March 25). 14 states ask U.S. to revise some education law rules. New York Times. Retrieved 2021

- Schemo, D. (2004b, August 17). Nation’s charter schools lagging Behind, U.S. test scores reveal. New York Times. Retrieved 2021

- Schoolboys of Barbiana. (1970). Letter to a teacher. New York: Random House.

- Shor; I., & Freier, P. (1987). A pedagogy for liberation. South Hadley, MA: Bergin & Garvey.

- Steinberg, J., & Henriques, D. (2001, May 21). When a test fails the schools, careers and reputations suffer. New York Times. Retrieved 2021

- Strauss, S. (2005a). Operation “No Child Left Behind.” In B. Altwerger (Ed.), Reading for profit (pp.33-49). Protsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Toppo, G. (2005). Education Department paid commentator to promote law. USA Today, January 7, 2005. Retrieved 2021

- Wells, A. (2004, December 28). Charter schools: Lessons in limits. Washington Post

- Zinn, H. (2004, September 2). The optimism of uncertainty. The Nation.

- Zuhara, B. (2005, January 2). Literacy (R. Krishnan, Trans.). The Hindu, Literary Reviewer, pp.1-2.

Home: Literacy, media, literature, children's literature, & language arts